10 Groundbreaking Women Of Softball

10 Groundbreaking Women Of Softball

In honor of Women’s History Month, FloSoftball and Mark Allister compiled a list of ten groundbreaking women of softball.

Mark Allister is the author of Women’s College Softball on the Rise: A Season Inside the Game. He welcomes story ideas and comments at allister@stolaf.edu.

In honor of Women’s History Month (March), FloSoftball Senior Editor Chez Sievers and I compiled a list of ten groundbreaking women in softball. Three began playing softball before colleges were offering scholarships to female athletes; most are from the post-Title IX era. We hope that older fans will recall some of their favorites and that younger fans will learn something about the history of the game. We know that this list of groundbreaking women to be much longer, but we will continue to recognize more of these women for years to come.

Joan Joyce

Great in numerous sports, Joyce has the credentials to be considered a top-five female athlete of all time. Her competitiveness and physical prowess allowed her to excel casually against all-comers in ping-pong, pool, and bowling; while in college, she was a member of the U.S. national team in basketball and set a single-game AAU scoring record in 1964 with sixty-seven points; she played for and coached national volleyball teams; at age thirty-five she took up golf, became a member of the LPGA in 1977, and in 1984 was top-65 on the money list. And she dominated women’s softball in her prime.

Before Title-IX, when women’s college softball was primarily a club sport, the best players suited up for town teams competing in the Amateur Softball Association. The ASA formed leagues, held a national championship, and named All-American teams. In her twenty-year amateur career, Joyce played three years for the powerhouse Orange (CA) Lionettes and seventeen years for the nationally dominant Raybestos Brakettes based in Stratford, Connecticut. As a hitter, Joyce compiled a lifetime batting average of .327, but she was named to the ASA All-America team 18 straight years and was MVP eight times because of her pitching. Her lifetime stats: 753-42 win-loss record, 150 no-hitters, fifty perfect games, a record forty-two wins in a season that included 38 shutouts, and a lifetime ERA of 0.09.

In 1994, at an age when many people are retiring, Joan Joyce became the women’s head softball coach at Florida Atlantic University, building the program from scratch into a perennial NCAA tournament team.

For all her exploits, one night, in particular, enlarges her groundbreaking role. In 1961, the young Joan Joyce faced off against the legendary Hall of Fame baseball player, Ted Williams, who had retired the year before. Many people believe that Williams is the greatest hitter to ever play major league baseball, but that night he was going to try something different, to hit a softball pitcher.

The occasion was a fundraiser for children suffering from cancer. A crowd estimated at 17,000 people filled the Brakettes ballpark and spilled onto the field, ten rows deep. Joyce threw ball after ball past Williams, who was able only to foul off a couple of pitches before he set his bat down and walked away. Newspaper stories about the event were read by sports fans who didn’t even know that women played fastpitch softball.

Sharron Backus

Like Joan Joyce, Backus starred during the heyday of town teams that competed in the Amateur Softball Association. From her shortstop position, Backus led teams to seven championships during her playing career from 1961-1975, including the Whittier Gold Sox in 1961 (when she was only fifteen years old!) and the Brakettes in the last five years of her career. Her early years playing for town teams overlapped with her college playing days at Fullerton College (known now as Cal State Fullerton) from 1964-67.

Though Backus was a great amateur player, she is best known for her tenure as head coach at UCLA from 1975 to 1997. After women's softball became an NCAA sport in 1982, Backus' teams won eight of the first fourteen NCAA softball championships. At the time of her retirement, she was the winningest college softball coach in history and had established UCLA as the dominant college program. She also began what has come to be called the UCLA coaching tree.

UCLA’s first All-American softball player, Sue Enquist, starred for Backus from 1975 to 1978. After college, Enquist would go on to help lead the Brakettes to four ASA championships before joining her mentor as an assistant coach in 1980, assuming co-head coaching responsibilities in 1989. Following Backus’ retirement, Enquist became head coach, a position she held until 2006, when after three national championships she stepped down and handed off the job to Kelly Inouye-Perez, who had played for Backus and Enquist in the 1990s and had herself become an assistant coach. Inouye-Perez has led UCLA to two more national collegiate titles.

Margie Wright

Wright grew up in the small town of Warrensburg, Illinois, and joined her local ASA softball team at age ten, when she had to lie about her age because the minimum age was twelve. She attended Illinois State University, and among her exploits there, she led the Redbirds in 1973 to the Women’s College World Series of the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW), which had been founded in 1971 to govern collegiate women's athletics in the United States and to administer national championships. On the final day, Wright threw a complete game, 5-1 win against Southwest Missouri State, then shut out Arizona State 4-0 to get her team to the final game, before pitching all sixteen innings (thirty total for the day) in the title game, which Illinois State lost to Arizona State, 4-3. As punishment for throwing thirty innings in one day, Wright was suspended by a three-woman Illinois sports commission from pitching in any game in her upcoming senior season! The commission also banned the Illinois State softball team from post-season play in 1974.

After six years as head coach at Illinois State, Wright was hired away by Fresno State, and she turned the Bulldogs into a national powerhouse. In every one of her twenty-seven seasons, Wright led Fresno State to the NCAA tournament. In their ten trips to the Women's College World Series, the Bulldogs won a national title in 1998 and were runners-up three other times. At the time of her retirement in 2012, Wright was the winningest softball coach in NCAA history.

In the decades following the passage of Title IX in 1972, a softball team typically played on fields sub-standard to the school’s baseball facilities. College administrators rarely believed that female athletes deserved good facilities or that fans would want to watch the games. Margie Wright helped change that. By the early 1990s, Fresno State’s great success had led to fan support that had outgrown the capacity of their previous field, which didn’t even have lights. Wright formed a committee of Fresno business people to fundraise for a new field, but the university’s president refused to support the project. In a lucky break for women’s softball, Fresno State had been randomly selected for review regarding Title IX by the Office for Civil Rights (OCR). The administration turned in some false answers, and when the OCR found out, they declared Fresno State University out of compliance with Title IX. Fueled by her belief that female athletes should have comparable resources to male athletes, Wright argued to the university that building a softball stadium comparable to the baseball stadium would show compliance.

Bulldog Diamond, the modern forerunner to today’s stadiums, debuted in 1996. The $3.2 million softball stadium featured nearly 1700 permanent seat-back chairs, sunken dugouts, lights, concessions stands, restrooms, practice areas, enclosed batting cages, a press box, and a scoreboard. Fans showed up in droves — demonstrating that women’s sports could make money — with Fresno State setting attendance records for a season and for individual games. With temporary bleacher seats erected, the team drew more than 5,000 fans when they played host to UCLA in 1996 and again in 1997, a year when the team’s average attendance was 2,557. Fresno State’s Bulldog Stadium got built because of Title IX pressures and Wright fighting for her female athletes against the desires of a male administration. Fittingly, the structure was renamed in 2014: Margie Wright Stadium.

Carol Hutchins

Carol Hutchins is the first of our groundbreaking women whose athletic talents could be rewarded with a college scholarship. During high school in Lansing, Michigan, Hutchins was an All-City basketball player for three years as well as a key member of the Lansing Laurels, an ASA fastpitch team that finished as high as fifth nationally. Hutchins attended Michigan State University, where she played on the Spartans varsity basketball and softball teams from 1976 to 1979.

Hutchins started at shortstop as a freshman and helped Michigan State win an AIAW National Softball Championship in 1976. Even more important to women’s sports is what she did as a basketball player. In 1978, the Spartans' men's team — including Magic Johnson — traveled to games via chartered buses or planes, ate at real restaurants, and slept two to a room; the women's team were driving themselves in station wagons, eating at McDonald's every meal, and sleeping four to a room. The women finally had had enough and sued the university for Title IX violations, as captain of the basketball team, Hutchins got her name on the lawsuit: Hutchins v. Board of Trustees of Michigan State University. Perhaps because of the lawsuit, conditions improved for the team and the case was settled favorably out-of-court in the 1980s. Unlike many female sports pioneers, Hutchins has not had to sue again under Title IX rules. But that battle would be only the first of many against sexism and gender inequity that she has fought.

Hutchins became the head coach of the Michigan softball team in 1985; she is still leading the program that she turned into a national power. Michigan has been to twelve Women's College World Series, and Hutchins’ 2005 team was the first from east of the Mississippi River to win the national title. In 2016 she passed Margie Wright for the most number of career wins as a head coach, and in the past two seasons, she and Mike Candrea from the University of Arizona have been trading back and forth that career mark. In 2016, Hutchins was the inaugural winner of the espnW Pat Summitt Coaching Award.

Hutch, as she’s known in the softball world, is a fierce proponent of the value of women’s sports and a fierce opponent to the sexism that seems never to end. One measure of what makes women’s college softball so special is that the victories and championships aren’t what people reference when they talk about her. The legendary Hutch has arisen because of the devotion she has from her former players and from fellow coaches. Hutch wants to win softball games — no one would dispute that — but she wants even more to mold girls who enter the Michigan program into confident, powerful, principled young women.

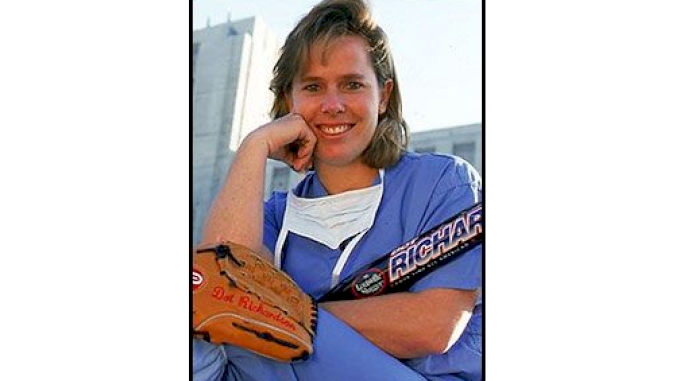

Dot Richardson

Like the other groundbreaking women on our list, Dot Richardson has had a long career in softball. At the age of 13, the precocious Dot joined the Orlando Rebels, becoming the youngest player ever to play in the ASA Women's Fast Pitch National Championships. In college, Richardson played for Western Illinois for one year before transferring to UCLA. A standout shortstop, Richardson won All-American honors every year and was so accomplished that she was later named the 1980's NCAA Player of the Decade.

Because women’s sports seldom lead to lucrative pro contracts, outstanding female athletes are expected still to achieve highly in the classroom, and Richardson was a model of the NCAA student-athlete. She graduated from UCLA with a degree in kinesiology, received a Masters's Degree in Exercise Physiology from Adelphi University in 1988, and an M.D. from Louisville in 1993. Midway through a post-doctoral residency in orthopedic surgery, Richardson joined the national softball team preparing for the Atlanta Olympics in 1996.

The Atlanta Olympic games are often considered the place where fast pitch women’s softball broke through to a general sports audience, and Richardson was the poster-child for the team, her charismatic face lighting up action photos. She hit the game-winning home run in the 1996 gold-medal game against China and then starred for the 2000 team that won gold again in Sydney. In addition to her Olympics participation, Richardson was a regular contributor to the United States’ international efforts: she played in five Pan American Games (1979, 1983, 1987, 1995, and 1999) and five World Championships (1982, 1986, 1990, 1994 and 1998).

After college, Richardson played ASA ball with the Raybestos Brakettes until 1994 and then ended her professional career with the California Commotion of Woodland Hills, California. She is a sixteen-time ASA All-American and was inducted into their Hall of Fame in 2006. Richardson is one of the most decorated collegiate, national, and international players in softball history.

Though for years Richardson tried to balance her softball and medical careers, in 2013 she accepted the head coaching job at Liberty University, where she has turned around the program and helped Liberty become a mid-major power.

Lisa Fernandez

Fernandez went to UCLA, was a four-time First Team All-American, and an Olympics star. If Fernandez hasn’t blazed any new trails, she is on this groundbreakers list as the player who perhaps has set the bar the highest for athletic achievement in the post-Title IX era. She is generally considered the greatest college softball player of all time.\

In 1993, Fernandez was coming off back-to-back Honda Awards, presented to the nation’s best softball player. But she outdid herself in her senior season at UCLA, winning the Honda-Broderick Cup, awarded to the country’s most outstanding collegiate female athlete. What did she do to win the award? She had perhaps the greatest individual season in softball history — she hit .509 with eleven home runs and forty-five RBI; in the circle, she went 33-3 with a 0.25 ERA. One of those losses was in the NCAA championship game, wherein an epic showdown between the two greatest programs and two of the greatest pitchers in the game, Arizona’s Susie Parra threw a two-hit shutout to best Fernandez and UCLA 1-0, with Fernandez giving up only one hit and no earned runs.

With a career mark of ninety-nine wins and seven losses, and a career ERA of 0.22 — all while playing in the nation’s top conference against other top teams — Fernandez would have been a candidate for G.O.A.T. based solely on her pitching record. But she was also one of the most feared hitters in softball, ending with a career batting average of .381 and hitting for power. She took her dual threats to the Olympics three times, and she holds the Olympic record with twenty-five strikeouts in a game and the highest batting average for a single tournament.

As a visible superstar in softball, Fernandez, who is of Puerto Rican-American descent, helped pave the way for what has come to be called the “Latina Explosion” in softball. Recent decades have seen high numbers of Latina softball players attending college and achieving highly in the classroom and on the playing fields.

Jennie Finch

Twice a Honda Award winner for best college softball player, three times a First Team All-American for Arizona, Jennie Finch was the dominant pitcher of her era, as well as a feared hitter. Spanning three seasons, from late in her sophomore year to early in her senior year, Finch never lost a game. She still holds the NCAA record with sixty straight wins.

From 1991 to 2007, Arizona, led by head coach Mike Candrea, won eight national titles, and their rivalry with UCLA was legendary. Finch helped Arizona to one of those championships (2001), as well as a runner-up finish. Her career stats are prolific — 119-16 won-loss record in the circle with a 1.08 career ERA; a .301 batting average to go with 195 RBI and fifty home runs.

After graduating from Arizona in 2003, Finch began playing for Team USA, getting ready for the upcoming Olympics. She went 15-0 in the month leading up to the 2004 Games and then continued her dominant form in Athens, winning two games while giving up only one hit and no runs.

Her college and Olympics success, along with her model looks, helped her in 2004 to be named one of People Magazine’s 50 Most Beautiful People. Glamour and Vanity Fair had features on her; she made a Sports Illustrated cover. In 2005 SI included her in their Swimsuit Issue, though she chose to have relatively modest photos. Finch turned down lucrative offers to pose for Playboy and Maxim, in part because of her Christian faith — she has on numerous occasions said that she wants to be a role model for girls and young women. In 2008, Time magazine declared Finch the most famous softball player in history. She was not the most decorated with individual honors (though she ranked high in that), but she was certainly the most known outside the game.

In the years that the fashion industry was interested in her, Finch continued her softball success. She joined the National Pro Fastpitch league in 2005. Playing for the Chicago Bandits, Finch had a fifteen consecutive games win streak at one point, and she still holds the league's season ERA crown, which she set in 2007. In 2008 she rejoined Team USA, winning two more games in the Beijing Olympics, once again giving up no runs.

In 2010, Finch retired from softball to focus on her family (she now has three children). But she has continued to be a great promoter for the sport. She guests at clinics and speaks to groups. In 2011, Finch co-authored the inspirational and best-selling Throw Like a Girl: How to Dream Big and Believe in Yourself, with Ann Killion. In August 2011, she started working at ESPN as a color commentator.

Finch has been a groundbreaker as well as a role model for how to balance a public and private life as a female athlete. Her coach at Arizona, Mike Candrea, sums up her impact well: "Jennie has transformed this sport, touched millions of young kids in many different ways – whether it's fashion, whether it's the way she plays the game – but through it all she's been very humble."

Jessica Mendoza

Like many players on this list, Mendoza was a four-time First Team All-American. Starring for Stanford University, she ended her career with fifty homers, 188 RBI, 230 runs scored, and a batting average of .416, but she wasn’t just a power-hitting outfielder. She could run (eighty-six career stolen bases) and defend. Mendoza duplicated those hitting numbers wherever she went, as a member of the women’s national team, in the Olympics in 2004 and 2008, and in the National Pro Fastpitch league.

Many young softball players know Mendoza more for her work announcing major league baseball than as a great softball player in the first decade of this century. After an ESPN interview when she was a player, Mendoza caught the eye of a producer who asked whether she had any interest in television. Several years later, in 2007, ESPN came calling, and she answered. Highly energetic, passionate, and articulate, Mendoza began as the lead softball analyst for the Women’s College World Series and a college football sideline reporter. She then worked as a reporter and analyst for the Men’s College World Series, as well as an analyst for the Little League World Series. When she quit playing softball professionally to focus on her ESPN work, her announcing roles grew.

Mendoza has been a trailblazer in her career as a sports announcer. In 2015, Mendoza became the first female ESPN Major League Baseball game analyst, during “Monday Night Baseball.” In 2016 ESPN named Mendoza as a regular member of the “Sunday Night Baseball” announcing team, which she did for four years. In 2020, Mendoza became the first female analyst to call the World Series on national radio, a series that became serendipitous for her.

Mendoza grew up in Southern California in a traditional Mexican-American family, and like many at the time, she was caught up in the “Fernando Mania” that swept the area when the Dodgers won the World Series in 1988, led by pitching great Fernando Valenzuela. Mendoza’s first major league game in person came as a young girl in Dodger Stadium watching Valenzuela — thirty-eight years later, she was calling the Dodgers next championship.

Natasha Watley

A four-time First Team All-American shortstop at UCLA, Watley owns most of the school’s career hitting records: hits (395), runs scored (252), at-bats (878), triples (21), and stolen bases (158). Her batting average of .450 is second all-time at UCLA and seventh in NCAA history. Watley’s best season was her senior year, when she led UCLA to the national title, won the Honda Sports Award as the nation's best softball player, and then was chosen as the Honda Cup winner as the nation's top female athlete. Very fast from the left side of the plate, Watley could also hit with power, notching ten home runs and fifty-three RBI that year. And her defensive range at shortstop is legendary.

Watley and her UCLA teammate Tairia Mims Flowers were the first African-Americans to play for Team USA softball in the Olympics, and Watley starred. During the “Aiming For Athens” tour in 2004, Watley hit .464 and then led the team with twelve hits at the Olympics to pace a gold-medal effort. In 2008 on the “Bound 4 Beijing” tour, Watley hit .450 and was the lead-off batter for Team USA in their silver-medal winning Olympics effort.

Watley followed her collegiate career by playing professionally when she wasn’t on duty with the national team. In the National Pro Fastpitch league, she was an All-Star seven times (playing mostly for the USSSA Pride) and became the first player in league history to amass 300 career hits (in 2014). She also played for Team Toyota in the world’s best professional league, the Japan Softball League, helping Team Toyota win five of six championships between 2010 and 2016.

Watley is a great ambassador for women’s softball, and among her many contributions is her creation of the Natasha Watley Foundation. Established in 2009, the foundation, in the words of its mission statement, “seeks to empower young women to make healthy lifestyle choices, develop strong self-esteem, and to become leaders of character through participation and training in the sport of softball.” Those words echo what many in softball attempt to do, but Watley’s foundation has an unusual core audience. Softball is expensive and suburban, and Watley’s goal is to create opportunities in softball for girls and young women in underserved communities.

The Packaged Deal

In 2013 three former collegiate players — catcher Jen Schroeder, pitcher Amanda Scarborough, and infielder Morgan Stuart — were at the same teaching clinic in Alberta, Canada, and on a plane ride home they brainstormed how they could bring the clinic experience to a much wider audience. Together with Katie Schroeder (Jen’s sister), they named themselves The Packaged Deal (TPD), put on their first clinic in 2014, and have since demonstrated how to use the internet and social media to bring softball and life lessons to many thousands of girls.

Jen Schroeder was one of the first former players to post instructional videos online as a way to reach girls far away from her Southern California home where she gave catching lessons. Adept at social media and connecting with girls, Schroeder created a “brand” for herself. TPD has continued such branding very successfully.

TPD instructs a large number of girls via on-line tools. As their website says, CLASS IS IN SESSION, and their Softball School is an online-based program with 100 live classes that girls can watch on-demand on their own devices. The outreach and the softball school also creates a large audience for their TPD clinics, which over the years have now grown to well over 300 thrown across the country.

All sports fans are used to seeing the big shoe and apparel companies sponsoring university teams, and in 2017 Nike signed TPD to a long-term apparel and shoe deal. TPD wears and sells Nike products at their clinics and on-line. Nike pays them. Such an arrangement would have been unimaginable ten years earlier, or even in 2017 without the creative efforts of Jen Schroeder, Katie Schroder, Amanda Scarborough, and Morgan Stuart. The four women who make up TPD are groundbreakers not because of their individual softball careers, as accomplished as they all were, but because they demonstrated how softball instruction could get beyond the traditional one-to-one coaching and how former players could become successful entrepreneurs, forging a different kind of career.

Related Content

Replay: Michigan St vs UNCW | Feb 28 @ 5 PM

Replay: Michigan St vs UNCW | Feb 28 @ 5 PMFeb 29, 2024

Replay: Michigan St vs Campbell | Feb 27 @ 4 PM

Replay: Michigan St vs Campbell | Feb 27 @ 4 PMFeb 27, 2024

Highlights: UCLA vs. Tennessee Softball | 2024 Mary Nutter Collegiate Classic

Highlights: UCLA vs. Tennessee Softball | 2024 Mary Nutter Collegiate ClassicFeb 27, 2024

Highlights: No. 19 UCLA vs. Baylor | 2024 Mary Nutter Collegiate Classic

Highlights: No. 19 UCLA vs. Baylor | 2024 Mary Nutter Collegiate ClassicFeb 26, 2024

UCLA Softball Recap: Bruins Upset Tennessee At Mary Nutter 2024

UCLA Softball Recap: Bruins Upset Tennessee At Mary Nutter 2024Feb 26, 2024

Replay: Yankee Field - 2024 Mary Nutter Collegiate Classic | Feb 25 @ 9 AM

Replay: Yankee Field - 2024 Mary Nutter Collegiate Classic | Feb 25 @ 9 AMFeb 26, 2024

San Diego vs UC Riverside - 2024 Mary Nutter Collegiate Classic

San Diego vs UC Riverside - 2024 Mary Nutter Collegiate ClassicFeb 26, 2024

Replay: Wrigley Field - 2024 Mary Nutter Collegiate Classic | Feb 25 @ 9 AM

Replay: Wrigley Field - 2024 Mary Nutter Collegiate Classic | Feb 25 @ 9 AMFeb 26, 2024

Replay: Fenway Field - 2024 Mary Nutter Collegiate Classic | Feb 25 @ 9 AM

Replay: Fenway Field - 2024 Mary Nutter Collegiate Classic | Feb 25 @ 9 AMFeb 26, 2024