A Conversation with Tatiana Lysenko

A Conversation with Tatiana Lysenko

Anyone who was a gymnastics fan in the early ’90s knows the name Tatiana Lysenko. Crisp and confident, Lysenko combined artistry with cutting-edge acrobati

Anyone who was a gymnastics fan in the early ’90s knows the name Tatiana Lysenko. Crisp and confident, Lysenko combined artistry with cutting-edge acrobatics, exemplifying the Soviet gymnastics tradition.

Born in Kherson, Ukraine, Lysenko trained under renowned coach Oleg Ostapenko and represented the USSR in international competition, winning the 1990 World Cup and team gold at the 1991 World Championships. After the Soviet Union dissolved in December 1991, she continued competing and was part of the Unified Team (composed of gymnasts from the former Soviet republics) that earned gold at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. During event finals, Lysenko performed an immaculate beam routine to clinch a second gold and also won the bronze on vault. From 1993–94, Lysenko represented the Ukraine, earning third all-around at the ’93 Worlds, first all-around at the ’93 World University Games, and fourth on vault at the ’94 Worlds.

Lysenko performed with ease elements that are still considered difficult today: a double layout and double Arabian on floor, mount sequence of roundoff-layout to two layouts on beam, double-twisting Yurchenko on vault, and Shaposhnikova on bars. She accented her difficulty with signature artistic touches, including a backspin and one-arm handstand on beam.

Having retired from competitive gymnastics in 1994, Lysenko moved to the United States two years later. She spent several years employed in the U.S. gymnastics world, performing in professional tours and working as a motivational speaker, summer-camp coach, and instructor of tumbling and ballet. In 2002, Lysenko enrolled in the University of San Francisco School of Law, graduating in 2005. She still lives in the Bay Area and currently works as an attorney in the field of legal discovery. Lysenko met her husband, Yogesh, who works in the technology industry, in California; the couple has a three-year-old daughter, Sophia.

During a trip to San Francisco earlier this year, I spoke with Lysenko about her career as one of the last in a long line of Soviet gymnastics greats.

How did you get started in gymnastics?

I was around four or five years old, and very small and very active. A woman who coached young gymnasts in Kherson saw me and said to my mother, “Your daughter would be perfect for gymnastics. Why don’t you bring her to my class?” In the Soviet Union, gymnastics was a state-sponsored activity. It was part of a culture of athleticism in which sports clubs were promoted and funded very well.

I started training at a club called “Dinamo,” where gymnasts began as early as four and went through a training and selection process as they got older. We’d meet twice a week for one or two hours each time. At six or so, I became part of a group of gymnasts who had been identified as having potential, as much as it is possible to identify potential at that age. Our training increased to approximately three times a week—still not intense, but a bit more focused.

You trained under Oleg Ostapenko for years. When did he become your coach?

I started training with Oleg when I was nine or ten years old. I was incredibly lucky to be at the right place at the right time. Oleg had been coaching in another part of the Soviet Union before circumstances brought him to Dinamo in Kherson. When I asked him many years later what it was like to begin coaching me and the other four girls in my group, he said, “I looked at all of you, and thought, ‘Oh my goodness, nothing is going to work out here.’” He had already trained national-level athletes, and had to start over completely with us. It was very fortunate for me.

At that time, some of the girls on my small team were already learning more difficult skills, like giants on bars. When Oleg came in, he said, “Stop everything.” He saw that we had learned techniques designed to get a particular skill done—not to build a proper progression so we could learn more in the future. We stopped and redid everything, going through all the basics: forward rolls, handstands, kips, swings. I hadn’t started learning difficult skills yet, so it was great to know that I wasn’t going to be rushed into learning new skills. And looking back now, I think that was the best thing that could have happened to me. I built a strong foundation.

What was he like as a coach?

On one hand, we trained very hard; he was demanding and had extremely high standards for what he expected from us. He would rarely say something was good. Usually, there was a long list of criticism—always constructive, but he would rarely praise his gymnasts outright. When he said “OK” or nodded his head, that was huge praise. On the other hand, bad days in the gym didn’t trickle over into the rest of my life. He never made me feel upset because something had been difficult during training. He was very positive, and even though I was young, he treated me as a mature individual capable of knowing of what was right. He didn’t micromanage what I had for dinner, or when I went to bed. He was a mentor as opposed to an enforcer, and I feel incredibly lucky for that.

How did you move up within the ranks of the Soviet team?

Within a couple years, my teammates and I began attending training camps at the Dinamo center in Moscow. We also participated in national Dinamo competitions. Based on our placement in those competitions, four of us were invited to attend the USSR junior national training camps at Round Lake Training Center, located about an hour outside of Moscow. It’s surreal to think of it now, but we took 22-hour train rides from Kherson to Moscow. After boarding the train in the early afternoon, my teammates and I would chat, joke around, do word puzzles. It was a chance to relax and be children. I remember those times very fondly.

Did Moscow eventually become your full-time home?

Sometimes I’d stay at Round Lake for three months straight, but I never formally relocated there. My small gym in Kherson remained my hometown gym, and I’d go back home whenever there was a break in the Round Lake training schedule.

I’d love to learn more about the training at Round Lake.

Individual coaches traveled to the training camps with their athletes, and there was always a national team head coach overseeing the training sessions. During my time, the head coach was Alexander Alexandrov. The national team also provided a tumbling coach, balance beam coach, and dance instructor. Our individual coaches rotated with us through all the events. There were usually three training sessions a day, totaling over eight hours. There were only two morning sessions on Wednesday and Saturday, and we had Sundays off.

What are your strongest memories of Round Lake?

There is one thing that stands out vividly in my mind. During the Moscow winters, which are incredibly cold, with thick layers of snow on the ground, we’d get up at 7 a.m. for our morning workout. The sky would be pitch-black. We’d line up in front of our dorm, about a half-mile from the gym. Then we would have to run around the perimeter of the training center and make our way to the gym. I can’t tell you how many tears I shed during those runs. The cold air made it nearly impossible to breathe, and the snow made it difficult to even move. We’d arrive at the gym, quickly change, start an hour-long workout, and then have breakfast.

Did the hard work ever become overwhelming?

There were certainly challenges, but being part of that environment motivated me to continue. I always viewed it as a special privilege and achievement to be selected as part of that core group of top athletes, alongside all the legendary gymnasts from the Soviet era. As a young girl trying to find my spot there, I wanted to show my very best. Those runs stand out in my memory, but I would never have been discouraged by something like cold weather or running in the morning.

I am also very lucky to have amazingly loving and supportive parents. During those years they provided me with the kind of nurturing and caring environment that allowed me to recover both mentally and physically from time away from home and from the grueling training. They put things into perspective and gave me a sense of worth that was independent from my success as a gymnast, which made a huge difference in how I was able to cope with all the ups and downs of life as a competitive athlete.

I can imagine that it was a lot of pressure.

Our program was so strong that it was more challenging to prove that you belonged on the team than to prove to the rest of the world that you should win an event. Between 1990 and 1992, every move you made was critical, and you could never rest on your laurels. And not only did your performance in competitions matter, but every mock meet, every training session was critical. It was a very intense period in my life. For example, one day in training, as I was preparing to do my balance beam routine, Alexandrov walked up and said, “OK, if you stick this one, you’re in.” It was sort of a joke, but the pressure was on immediately. No one told me that I would be evaluated by the head coach on that day at that time. I did nail it, thankfully.

Could you tell me about your path to the 1992 Olympics?

My first major competition was the 1990 Goodwill Games in Seattle. I did well in the team competition, which we won, but was not part of the individual competition.

Then you won the World Cup in Brussels.

Yes, that was the next step, and I had good performances. I proved that I truly did deserve a spot on the team.

And you competed at the 1991 World Championships in Indianapolis, a competition that many feel you could have won.

Oh, yes, I should talk about the ’91 Worlds, which was a traumatic experience for me. I had a good performance in the team competition and qualified for the all-around final. On my second event, balance beam, I made a completely unexpected mistake, missing my foot on the dismount. It was a shock, especially considering that I had a very difficult mount at the time—a layout-on to two layouts—and the dismount was just a roundoff, double back. I used to train that dismount early in the morning, right after the run in the snow, and never had a problem with it. It was just one of those mistakes. I was dazed, still trying to process the fall, as I prepared for my final two events. I made it through floor, but had lost all energy by the time I got to vault. I remember falling on at least one of the vaults.

How did you handle the disappointment and how did your coach react?

It was devastating, and I lost some confidence. Oleg was very supportive. I’m sure he knew that I was angry at myself, and he didn’t want to exacerbate the situation. But the worst was actually to come. I had qualified for the bars final, and as much as I was shaken by my experience in the all-around, it was decided that I should go ahead and compete. In retrospect, I wish I had not. During the final, when I did my overshoot to the low bar, I landed with my hands slightly off center on top of the bar. I tried to do a kip and my right hand gave out. I couldn’t have continued even if I had wanted to, so I stepped back and walked away—it wasn’t a time for drama or crying. I showed Oleg my hand, which had blown out like a pillow.

Did you leave the arena for treatment?

I was taken to what seemed to be a local emergency room set up to receive foreign athletes injured at the event. It was busy and full of regular patients. After we waited for some time, the x-rays were taken, showing spiral fractures in four of my metacarpals. The doctor put a cast on my hand and said that it would need to be replaced in a few days as the swelling went down. I was in tremendous pain and given Novocaine shots by the team doctor, but did not have any follow-up care in Indianapolis.

My team did not go straight to Moscow following the worlds as we had a follow-up invitational somewhere in Europe. I went along because the flights and hotels had already been booked. After arriving home a couple weeks later, I was seen by an orthopedic surgeon. X-rays showed that the bones had begun to grow together but that some pieces had twisted slightly at the time of injury. He told me that based on the original x-rays, my bones should have been reset so they would heal and grow properly, since I was only 16. That would have required surgery to insert screws and a follow-up surgery to remove them. He explained that it was too late at that point because the bones had already started to grow together and that I had to hope I would not have problems with the use of my hand in the future.

Ironically, had the correct procedure been done, there was no chance I could have recovered in time to resume training on uneven bars and prepare for the Olympic Games less than a year away. As it happened, I had my cast on for only a month and a half, and I am fortunate not to have any problems with my hand now.

How did you stay in shape while recovering?

I have to give credit to Oleg. He didn’t tell me “you’re done for,” although maybe some people thought I was. He said, “We’re going to use this time to go back to basics and polish up the things you can do.” Once the cast was off, I could instantly do a tremendous amount of work even without the use of one hand. I would do one-handed roundoffs into back layouts or other tumbling skills. I focused on ballet, learned new floor choreography, and polished my flight elements on beam.

It gave me a break from all the pressure and a chance to start over. Because my coach had faith in me, we just went along with the program, showing how much I could still do. I never lost my fitness level, and I emerged from that time energized and eager to prove that I was back. I could do all my skills, and I had a new beam mount: a one-arm handstand instead of the roundoff-layouts. I loved the change—I was able to start the routine with something beautiful and then move on, instead of knowing that I could immediately fall off.

How did the team leadership decide who was going to Barcelona?

The results of prior competitions and internal mock meets were part of the selection process, but there were many other elements that went into the decision. We had a training camp in Italy immediately prior to the Olympics, and there were at least ten gymnasts there. We were all just as good—we all could have been part of that team. I can’t remember precisely when the lineup was named, but it was during that time in Italy. And, of course, I might not have known a lot of things, and I’m sure I don’t know what our head coach thought. Perhaps I was doubted up until the very last day—I don’t know. Luckily, they kept me on the team.

How would you rate your Barcelona experience? Were you disappointed not to medal in the all-around?

There were no disappointments. I won a gold medal with my team at the Olympics. How can anything be disappointing after that? I nailed my routines during the all-around final, except for a step out of bounds on floor. Sure, it was a mistake, but when you compete in the Olympic all-around, it’s a gamble that every element will be correct at that exact time—it’s like throwing a dice. And, of course, as I knew very well, during any event, something can go terribly wrong. None of that happened, and I had a great event. And then to do so well on vault and beam in the event finals—it was terrific.

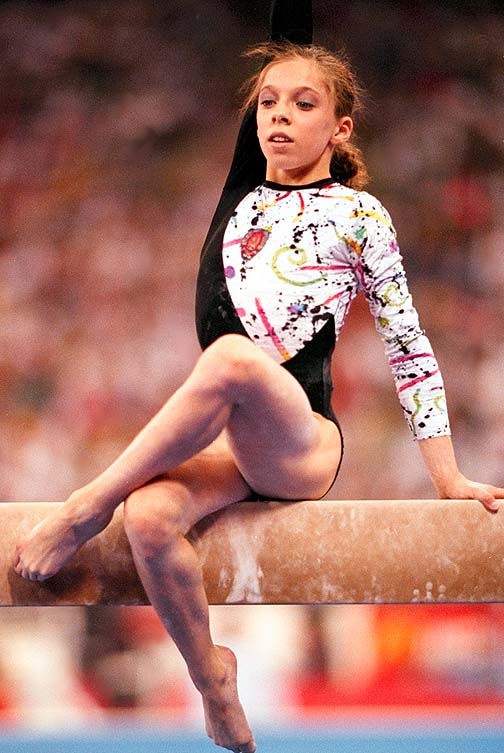

You placed third on vault, then won gold on beam. So many people remember that beam routine—weren’t you last to go?

Yes.

You appeared so calm and composed—did you feel that way?

I did, actually. Beam is so unpredictable that I knew not to expect anything. In the back gym, I stayed on the beam, doing back handsprings, walking back and forth, so that I would stay warmed up and ready. I didn’t watch the competitors before me. I told myself, “When it’s my turn I’ll go out there and do my regular routine.”

And then the routine was nearly flawless. When the score flashed, did you know immediately that you had won?

I didn’t, but I knew that I hadn’t made any mistakes. I felt that I lived up to my potential—that I had done my best routine. I was already extremely happy. And then to know that it was good enough for gold—that was incredible.

During vault finals, you did a double-twisting Yurchenko and took a step. At the time, a single-twisting Yurchenko and a double were both valued out of a 10. Do you ever look back and regret not using the simpler vault?

No, I’m so glad I did it. I would have felt so much worse if I did just a full and still took a step. I would have thought, “How silly was that?” No matter how safe you play it, there’s never a guarantee that you will not make a mistake. And taking risks like that was part of our team philosophy: the idea that if you could do something, you should do it—you should show it to the world. It wasn’t about playing a game of points or determining how to use the Code to your advantage. It was about showing the best gymnastics that you could in a pure sense.

The 1992 Olympics marked the end of the Soviet gymnastics dynasty. Did you think about that as you competed?

I did. The ’92 Olympics are special to me because I knew that there was not going to be a Soviet team anymore. The country disbanded in ’91 so we competed as the Commonwealth of Independent States, also called the Unified Team. We were the last of the Mohicans, the last gymnasts representing the legacy of Soviet greats. It was clear that things were never going to be the same, so it was a privilege to be a part of that team.

In the team event, we represented the legacy of the USSR; in the individual events, I officially represented the Ukraine, my new, independent country. When does that happen again? It was a fascinating time.

After the Olympics, you decided to continue competing.

Between ’92 and ’93, there was a period of flux. My 1992 Olympic teammates and I continued to train at Round Lake, but only for the Olympic follow-up events, like exhibitions or tours. At some point, we relocated to the Dinamo club in Moscow. Also at that time, I graduated high school and enrolled in the Ukrainian State University of Physical Education and Sports. I began training partly in Ukraine, partly in Moscow, while also focusing on my studies. As a veteran, I was welcomed with open arms to become a member of the Ukrainian national team. There was no selection process—I simply had to show respectable performances and represent the team with dignity. And I was fortunate to do that at the ’93 Worlds.

You placed third all-around, and could have won had you not stepped out of bounds on floor.

It was a great experience. After the enormous pressure of the ’92 Olympics, that year of preparing for the worlds was so much fun. I just had to stay in shape and keep up with my skills—the training was not nearly as grueling. Perhaps I should have trained a bit harder, then I might have won, but I was very happy with the result. That was really my last full-on competition—when gymnastics was still very, very important to me. Slowly, I came to the realization that I probably would not push myself to the ’96 Olympics. On the Ukrainian national team, there was a lot of attention paid to developing the younger athletes. The gymnasts of my generation now had other commitments and interests—we were focusing on our education, planning our future, and simply enjoying all that life had to offer.

My last competition was the ’94 Brisbane Worlds. I didn’t do very well; I had a silly fall on my beam dismount during the all-around. I took a step, my knees buckled, and I put my hands down. But I didn’t dwell on it. I had a lot of fun performing my new floor routine. I had asked a friend, rhythmic gymnastics great Oksana Skaldina, to choreograph it for me. The music was by French composer Jean Michel Jarre. For the first time, my floor choreography was fully my own initiative, and it was an awesome routine. In terms of the score I got or how well I performed my tumbling, it didn’t really matter—I had the opportunity to express myself and do something different. After Brisbane, I decided that there was no need to continue pushing towards these large-scale competitions and that I should focus on the next chapter of my life.

Twenty years later, gymnastics fans remember your routines vividly and many refer to you as one of their favorite athletes of all time. How does it feel to know that people still appreciate what you did back then?

It’s amazing to know that. It’s very special, and I am so thankful for the support. I can’t believe that people remember what I did so long ago.

Did you look up to anyone while you were a young gymnast in Kherson?

Yes, certainly. I’ll always remember my idols no matter how much time passes. I looked up to all the great Soviet champions, from Latynina, Tourischeva, and Korbut, to Shaposhnikova, Omelianchik, Shushunova, and Mostepanova. It was an honor to follow in their footsteps.

Lysenko winning Olympic gold on beam: